Are Montessori Schools Really the Best Option for Children?

The research behind Montessori schools and methods

Source: Pexels/ Tatiana Syrikova

When I was choosing a preschool for my first child, I remember visiting a Montessori school and being just completely blown away. Every toddler in the room was independently and meticulously doing their “work” and, when they were finished, they diligently cleaned up after themselves without being reminded by a teacher or even the “clean up” song. Most strikingly, I was in a room full of toddlers yet it was so quiet that I could hear a pin drop. I couldn’t help but wonder what spell these toddlers were under and how I could get my own toddler under this spell.

Although I ended up choosing a more conventional, play-based preschool for my child (mostly due to factors of convenience), I still think back to the Montessori preschool with awe. In recent years, the popularity of Montessori schools, Montessori play materials, and Montessori Instagram accounts seems to be exploding. Even Jeff Bezos recently donated two billion dollars to create a network of tuition-free Montessori preschools.

So does Montessori education really live up to all of this hype? Today’s newsletter will dive into the research on Montessori education and try to identify which parts of the Montessori method are backed by research.

What is Montessori Education?

Maria Montessori was an Italian physician who developed a specific educational philosophy around 1900 that has since developed into a popular method of education used in schools and early childhood education centers throughout the world.

In Montessori education, children learn through hands-on play involving a very specific set of materials. Most play occurs individually or in small groups. The children are allowed the freedom to explore all materials and allowed to choose what they engage with and how they engage with it. The classroom does not involve any types of rewards or punishments. The teacher guides and assists children as needed but does not provide direct instruction for the most part. Montessori classrooms focus on teaching children to independently complete activities of daily living and use “real” objects that adults use. Montessori focuses on the development of the whole child rather than focusing only on academic skills.

Research on Montessori

Before even beginning to review the research, it is important to explain that this research is limited. It is difficult to study an educational approach like Montessori for several reasons. Most importantly, the families that choose Montessori are very different from the families that do not. Families that choose Montessori schools are more likely to be higher socioeconomic classes and less likely to be an ethnic minority. Even public Montessori schools are more likely to include families from higher socioeconomic classes. Because of these limitations, it is important that we focus only on the studies that take family factors out of the equation, such as randomized controlled trials and lottery studies.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Because the families that choose Montessori are so different, the best way to study Montessori schools outside of the influence of these family factors is to randomly assign families to attend Montessori or traditional schools. These studies effectively eliminate the problem of families choosing Montessori schools being different from families who do not.

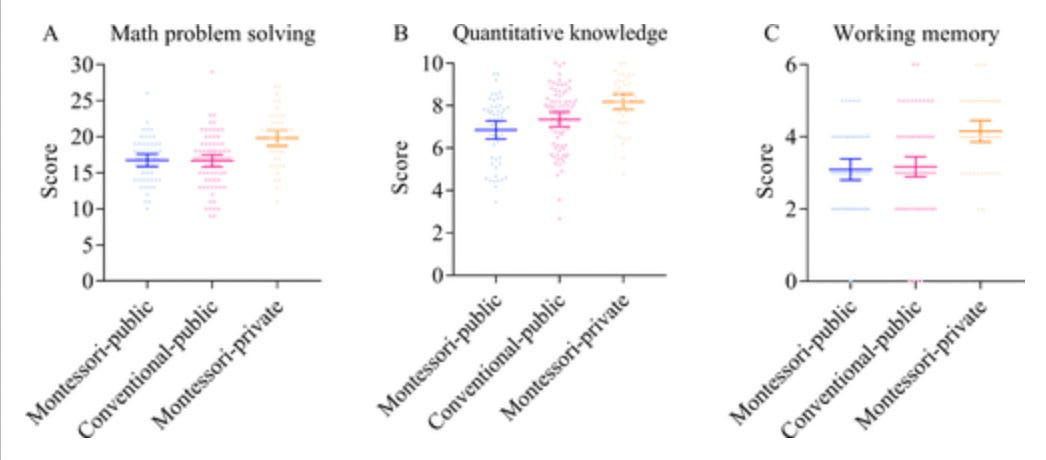

The most recent study was a randomized controlled trial of Montessori schools in France published in 2021. In this study, children were randomly assigned to a Montessori or conventional preschool classroom. The researchers found that children in Montessori preschool scored higher in reading than children in conventional preschool but found no differences between the children who attended Montessori versus conventional school on any other measure of language, math, executive functioning, or social skills (see below for the results). However, the teachers in this study lacked formal Montessori training, the curriculum was adapted (for example, daily work periods were shorter than 3 hours), and the preschools included some toys and materials that were not specifically Montessori materials.

Source: Courtier et al., (2021). Effects of montessori education on the academic, cognitive, and social development of disadvantaged preschoolers: a randomized controlled study in the French public‐school system. Child Development, 92(5), 2069-2088.

Two older studies from the 1970’s randomly assigned children to either a Montessori classroom or a conventional preschool Head Start classroom and both studies found no benefit for the Montessori method over conventional methods initially (see here and here). Yet when the researchers followed up with the children later, they found some small effects. The first study found better academic skills and higher IQ in boys, but not girls, who attended Montessori schools. In the second study, children in the Montessori program were more likely to graduate high school and less likely to be held back. However, both of these programs did not strictly adhere to Montessori methods and involved relatively small sample sizes.

Lottery Studies

Another way to study the quality of Montessori schools is to look at children who get into a Montessori school through a lottery system. These studies involve publicly funded Montessori schools that have more interested families than spaces available and children are randomly chosen through a lottery system to attend the school. The researchers then compared the children who wanted to attend the school and were chosen by the lottery to attend the school to the children who wanted to attend the school but were not chosen by the lottery to attend the school. These studies should also eliminate the problem of families who are interested in Montessori schools being different from families who are not.

First, researchers compared preschoolers (3 to 6 years old) who were randomly selected by a lottery to attend one Montessori school versus those who were not selected to attend the school. They found that the children in the Montessori school showed better reading and math, improved social skills, and advanced executive functioning by the end of kindergarten. They also showed more creative writing and reported more of a sense of a school community. However, this study only included one school so it could simply mean that this one Montessori school was higher quality rather than all Montessori schools being higher quality.

The researchers then expanded upon this previous study by including two Montessori schools and more children. The researchers found no difference between the two groups at the first test point of the study. Yet, three years later, the Montessori students showed greater growth in academic skills, social skills (theory of mind), mastery orientation (focus on learning rather than performing for others), and liking of school tasks. No difference was found in social problem-solving or creativity. Differences in executive functioning were only found at one time point. They also found that Montessori may reduce the income gap (fewer differences were found between high and low income students in academic skills in the Montessori schools).

However, it is important to note that all parents in this study were seeking out a Montessori school, suggesting this sample may not represent the population as a whole (that is, these parents may have all been more educated or involved than the average parent).

TRANSLATION: Research finds that Montessori schools may provide an advantage in some areas and finds no difference between Montessori schools and conventional schools in other areas and the results are not consistent across studies. It seems clear from the research that Montessori schools do not provide a disadvantage. However, we need additional research before we can conclude that Montessori provides a clear advantage.

Limitations of this Research

Why are these results so mixed and why is it still soon to conclude that Montessori education provides a distinct advantage?

Every school varies in how closely they follow Montessori principles.

In some of the studies detailed above, Montessori principles were followed very closely and in others they weren’t and this may make a big difference. Research finds that Montessori classrooms that more strictly follow Montessori principles were associated with more advances in executive function, reading, math, vocabulary and social problem-solving over the school year when compared to students in schools that use some Montessori methods and some non-Montessori methods. However, students were not randomly assigned in this study and it is very possible that the families who chose the school that strictly followed Montessori principles had other advantages. Regardless, it makes it difficult to apply this research to your local Montessori school. Montessori is not a trademarked term. Any school can call themselves “Montessori” without following any of the Montessori principles. If you are concerned about the quality of your local school, look for a school that is Association Montessori Internationale (AMI) or American Montessori Society (AMS) certified or has teachers certified through a program accredited by Montessori Accreditation Council for Teacher Education.It is unclear whether it is a particular aspect of Montessori or the approach as a whole that causes any significant findings. The research we have thus far doesn’t allow us to determine whether it is simply one part of Montessori education (such as play-based learning or a more organized classroom) that results in an advantage for children in Montessori schools or whether it is the Montessori approach as a whole.

The type of teachers who choose to teach at Montessori schools may be different. It is very possible that teachers who choose to work at Montessori schools have other qualities that make them higher-quality teachers. Most previous studies have not examined teacher quality so we do not know the extent to which this factor has played a role. Most teachers in the Montessori schools in these studies also had specialized training in Montessori education (a course that takes about 9 months to complete) and it might be that any type of specialized training (whether Montessori or not) improves teachers effectiveness and thus the quality of education. It may also be that teachers who choose to complete specialized training are different in some way from teachers who do not choose to complete this training (perhaps more committed to improving their teaching skills).

Do You Need To Buy Only Montessori Toys for Your Child/Have a Montessori playroom?

Creating a Montessori-approved playroom in your home is very “hot” right now, particularly on social media. It is hard to deny that the wooden, simple Montessori toys arranged precisely on shelves are more aesthetically pleasing than the jumbled heap of plastic toys in most playrooms. Yet, Montessori toys are typically very expensive, sometimes costing twice as much as their plastic counterparts.

There is some research suggesting there may be something “special” about Montessori toys. Research suggests that the more Montessori materials that schools use, the more children show advances in reading, vocabulary, and executive functioning over the course of the year. Yet, this study is only correlational and there are likely other differences between a classroom that only includes Montessori materials and those that don’t (such as more trained teachers or having more resources). Another study found that if they removed non-Montessori materials from classes that had some Montessori materials and some non-Montessori materials, children showed improved letter-word identification and executive functioning (yet no differences were found for vocabulary, perspective-taking, math, or social skills). Yet, this study relied upon the teachers agreeing to remove the non-Montessori materials and the teachers that agreed to remove Montessori materials may be different from the teachers that did not.

Are Montessori toys superior in any way based on the research we have about toys more generally? Not necessarily. In Montessori education, the materials provided are self-correcting meaning they are meant to be used in one way and they give the child immediate feedback when used incorrectly. An example of this is the Pink Tower toy used in many Montessori classrooms (see below)— if children place the wrong sized block on the tower it will topple over. However, research suggests that “open-ended” toys are associated with the most high-quality play (see the TIMPANI study (Toys that Inspire Mindful Play And Nurture Imagination). An open-ended toy is a toy that can be used in many different ways and does not suggest to children exactly how to use it. These types of toys inspire children to be more creative and flexible and play in new and different ways. They also tend to hold children’s attention for longer time periods. Yet, proponents of Montessori would argue that “close-ended toys” help to build self-regulation abilities and help children to learn specific skills.

It is also important to note that many toys marketed as “Montessori” are not actually Montessori-approved materials. As mentioned above, Montessori is not a trademarked term so any toy seller can claim their toys are “Montessori” with no basis whatsoever.

TRANSLATION: We do not yet have evidence that it is necessary or even ideal to outfit your playroom with exclusively Montessori toys. We need more research on toys before we can make that conclusion.

Overall Translation

We do not have evidence that Montessori schools provide a particular advantage over other educational approaches. Maria Montessori had incredible ideas that revolutionized early education and many high-quality preschools now emulate Montessori classrooms. However, Montessori schools are usually more expensive and more likely to be private than conventional schools. If a Montessori school fits into your budget and seems right for your child and your family’s needs, this may be a great choice for your family. However, if a Montessori school is out of your budget or doesn’t make sense for your family in other ways, you should feel good about choosing a non-Montessori school. Either way, it can be helpful to know which aspects of a Montessori school are supported by research and which aspects need more research.

The Aspects of Montessori Education Supported by Research:

Play-based learning. A key component of Montessori school is setting up an environment in which children can learn through play (although Montessori teachers refer to play as “work”). Research has found that play-based preschools tend to be associated with better long-term outcomes than preschools focusing on direct instruction of academic skills. Specifically, research finds that children in play-based preschools showed improved behavior and more social responsibility as teenagers and fewer work problems and arrests as adults, when compared to children in preschools involving teacher-led instruction of academic skills.

Assisted/enhanced discovery-based instruction. It isn’t just play-based learning in Montessori schools that makes a difference though but learning in which children discover concepts on their own through exploration, manipulation of materials, and experimentation (called discovery-based instruction in the research). Yet, this discovery is directed and scaffolded by teachers (referred to as assisted or enhanced discovery-based instruction). A meta-analysis reported that this type of instruction is more effective than other forms of instruction across 360 studies.

Learning involving hands-on sensory experiences. Montessori schools use concrete, hands-on learning strategies. This approach is backed by research, as research finds that learning is enhanced when presented across sensory modalities and when it involves hands-on experiences. Research also suggests that sensory experiences with letters improve reading.

Child-led learning. Child-led or child-initiated learning emphasizes student choice and autonomy. Montessori schools place a strong emphasis on child-led learning as the child chooses most learning activities. Research finds that this approach may help children to develop self-regulation abilities. Research also finds that when early childhood educators listen to students and allow more child involvement in learning, they tend to see better outcomes

Phonics-based instruction. In Montessori classrooms, children learn to read through multi-sensory experiences that stress phonics (that is, (sounding out the letters and blending the sounds together to form a word). Decades of research confirms that the phonics approach is optimal for early reading development. Many schools still use the “whole language approach” (determining the meaning of a word through memorization and context, such as relying on “sight words” or clues from the picture or the rest of the sentence) while research finds that this strategy is not as effective as phonics instruction in teaching children how to read. Check out this previous newsletter for more research on the most effective methods for teaching children how to read.

Organized and structured learning environment. Montessori classrooms are organized and structured in a very specific way (including a designated place for each object, designated areas of the classroom for particular learning activities, and minimal clutter or distractions). Indeed research finds that more organized and structured classroom environments are associated with better learning and children tend to do better when their classrooms are more organized.

The Aspects of Montessori Education the Research Is Less Clear On:

Mixed ages. Most Montessori classrooms include children of mixed ages (such as a 3- to 6-year-old classroom and a 6- to 9-year-old classroom) while conventional schools tend to group children who are within one year of age into grades. Research remains mixed as to whether mixed-age classrooms provide an advantage or disadvantage. Some studies find advantages such as more social interactions among children and others find disadvantages, including more negative interactions for younger children, less conversation for both older and younger children, and less engagement of older children. One “natural experiment” found that when a preschool transitioned from single-age to mixed-age classrooms, the 4-year-olds started acting more like 3-year-olds (shorter attention spans, less time focused on learning activities, less time with their peers than the teacher), while the 3-year-olds started acting more like 4-year-olds. A more recent study may help to clarify these mixed results. This study found that this effect was moderated by teacher education. In other words, older children were not as negatively impacted in a mixed-age classroom when the teacher was more educated (and could presumably balance the educational needs of different age groups). This research does suggest that parents may want to ask about the specific age composition of the classroom and be cautious if most children are younger than your child.

Lack of pretend play. Montessori schools do not encourage pretend play and do not include materials that lend themselves well to pretend or imaginative play while conventional schools often encourage pretend play through the use of materials such as doll houses and play kitchens. Montessori schools instead encourage play with realistic objects. Research has found that pretend play is associated with improved executive function, cognitive development, and social-emotional development. However, the quality of this research has been questioned by some researchers who argue we do not yet have evidence that pretend play actually results in these positive outcomes. Further research is definitely needed to determine whether pretend play should be incorporated into education.

Adaptation for neurodiverse children or children with learning differences. Maria Montessori first created Montessori education for children who were institutionalized for being “uneducable” and Maria Montessori reported that these children scored in “normal” levels on educational tests after attending her school. The American Montessori Society website also claims that Montessori education may be ideal for children with learning differences including dyslexia, autism, and ADHD. However, there is very little research on inclusion of children with learning differences and neurodiversity into Montessori classrooms and research has yet to determine the best methods for adapting Montessori education for children with learning differences or to rigorously compare Montessori to other methods for children with learning differences. In particular, Montessori classrooms may not be ideal for some children with autism who tend to engage in repetitive behavior instead of functional play.

Transition to secondary education.There are very few secondary education options (i.e., high schools) that follow the Montessori model so most children have to transition out of Montessori school to conventional education at some point before 8th grade. Research has yet to determine whether this transition is difficult for some students. Although research finds that children who attend Montessori school may have about the same GPA in high school as children who did not attend Montessori school, it may still be difficult for students to adjust to a different climate and expectations. Most high schools, colleges, and workplaces involve feedback on performance and rewards (whether it is grades, praise, or bonuses) and most do not allow you to follow your individual interests and/or work only on projects that you are motivated to do. Further research on this transition is needed.

Expert Reviewer

All Parenting Translator newsletters are reviewed by experts in the topic to make sure that they are as helpful and as accurate for parents as possible. Today’s newsletter was reviewed by two amazing reviewers.

Rebecca Berlin, PhD. Dr. Berlin has over 25 years of experience as an early intervention home visitor, special education teacher, inclusion teacher, autism specialist, school administrator, teacher preparation faculty member, and researcher. She specializes in supporting local, state and federal education systems and policies in meeting the needs of all children and families prenatal through eight. She now serves as the Executive Director of the Parenting Translator Foundation.

Jenicka Engler, Psy.D. Dr. Engler is a developmental neuropsychologist, researcher, and mother. She shares research-backed mental health, toddlers tips, and calls out parenting misinformation with a side of humor on her Instagram account.

Wondering how you can support Parenting Translator’s mission and/or express your gratitude for this service? It’s easy! All you have to do is share my newsletter with your friends and/or on your social media!

Thanks for reading the Parenting Translator newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive future newsletters and support my work.

Also please let me know any feedback you have or ideas for future newsletters!

Welcome to the Parenting Translator newsletter! I am Dr. Cara Goodwin, a licensed psychologist with a PhD in child psychology and mother to three children (currently an almost-2-year-old, 4-year-old, and 6-year-old). I specialize in taking all of the research that is out there related to parenting and child development and turning it into information that is accurate, relevant, and useful for parents! I recently turned these efforts into a non-profit organization since I believe that all parents deserve access to unbiased and free information. This means that I am only here to help YOU as a parent so please send along any feedback, topic suggestions, or questions that you have! You can also find me on Instagram @parentingtranslator, on TikTok @parentingtranslator, and my website (www.parentingtranslator.com).

DISCLAIMER: The information and advice in this newsletter is for educational purposes only and is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical, mental health, legal, or other professions. Call your medical, mental health professional, or 911 for all emergencies. Dr. Cara Goodwin is not liable for any advice or information provided in this newsletter.

Informative, susinct, useful. THANK YOU

This was super informative - thank you!