Teaching Your Child How to Read

The research-backed guide to how children learn to read and what you can do as a parent to help them

Source: Cottonbro/Pexels

When Should You Teach Your Child How to Read?

Research finds that children (even those at risk for reading disabilities) can be taught simple decoding of words as early as age 5 or even younger ages. Experimental research even finds that 3-year-olds can be taught to recognize or decode very simple words.

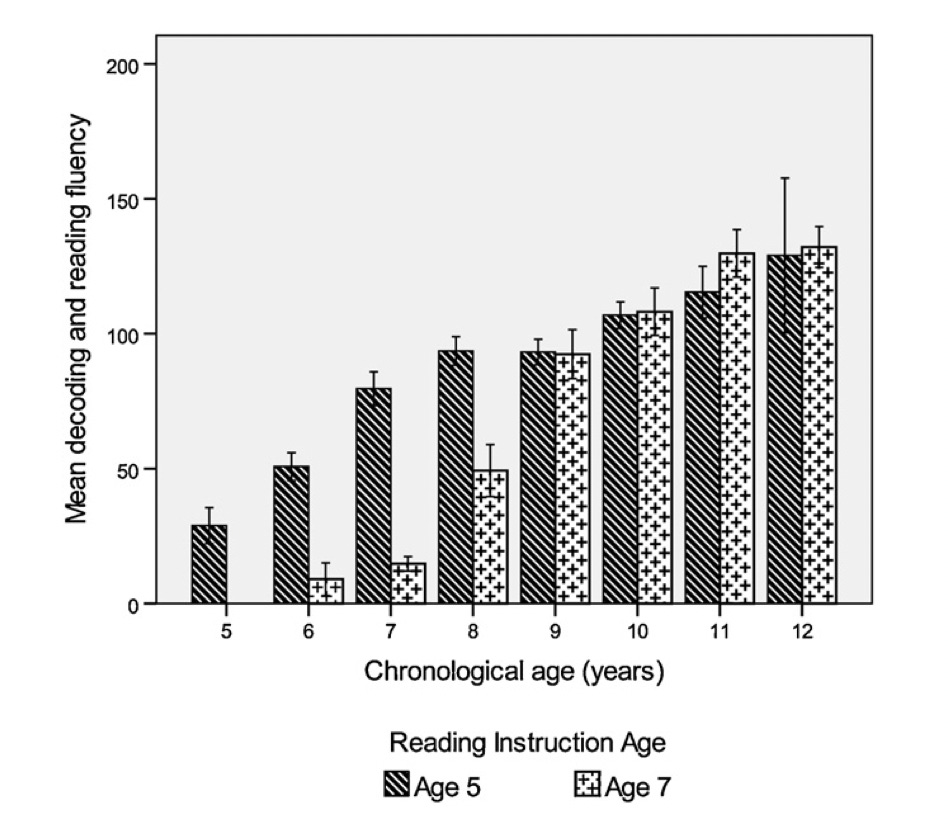

Yet, just because you can teach preschool-age children to read doesn’t necessarily mean you have to. One study examined children who were taught how to read around age 5 versus children who were taught to read around age 7. The children who were taught to read earlier initially showed better reading skills yet these differences faded by age 11 (see graph below). In middle school, no differences in reading fluency were found between the two groups. However, even the authors of this study state “we do not interpret the current findings as evidence that no reading instruction should occur before age seven.” They explain that their findings support the importance of helping children with the building blocks of reading (such as working on spoken language skills and awareness of letter-sound connections). It also important to mention that this study did not include disadvantaged families.

Source: Suggate,Schaughency, & Reese, 2012

Research has also examined the impact of when different countries start reading instruction and have found no impact of when children learn to read on reading at age 15 across 55 countries. For example, children in Finland and Estonia are typically not taught how to read until age 7 and the children rank 4th and 6th respectively on an international reading test. On the other hand, children in the US and UK are taught to read around age 5 and they score 24th and 21st respectively on the same test. This study also found that children who begin reading instruction earlier show greater variance in reading skills (meaning students in these countries are more likely to show both stronger reading skills and weaker reading skills). This may be because starting reading instruction at an age where some children are developmentally ready to read and some are not results in the children who are ready showing stronger skills and the children who are not ready experiencing frustration and perhaps even a hit to their academic self-esteem. However, it is important to mention that comparing across countries is problematic since there are many other differences among people from different countries, such as schools in English-speaking countries being more likely to teach children to read using less effective methods (the “whole language approach,” which will be described below) and schools such as those in Finland using a more effective phonics-based approach. In addition, research also suggests that English is a particularly difficult language to learn how to read and that learning to read in English may take twice as long as learning to read in other languages (such as Spanish and German).

TRANSLATION: This research suggests that you do not need to teach your child to read in preschool. If your child is interested in learning to read and they seem developmentally ready to read, you can start working with them on these skills. However, if trying to teach your child to read at a young age is causing you or your child undue frustration, do not stress about them “falling behind” and instead focus on play, conversation, and reading to your child during the preschool years.

Why Is Learning to Read So Hard?

Reading is not a natural process that our brains evolved to do, like learning how to speak. Learning to read literally involves a rewiring of the brain as the regions for processing written language have to learn how to coordinate and communicate with regions involved in processing spoken language. To learn how to read, children need to learn that an odd formation of lines and curves is associated with a particular sound and then learn how to blend those sounds together to make a word. They then have to connect that word with a meaning.

Because of this, nearly all children require specific instruction to learn how to read and do not learn to read just from exposure to books or you reading to them. For most children, learning to read requires a lot of instruction, hard work, and practice.

The Most Effective Way to Teach Children How To Read

For decades, researchers have debated whether children should be taught to read based on a “phonics” approach (sounding out the letters and blending the sounds together to form a word) or a “whole language approach” (determining the meaning of a word through memorization and context, such as relying on “sight words” or clues from the picture or the rest of the sentence). After decades of research, researchers believe that the phonics approach is optimal for early reading development. When children learn to read using phonics, it is easier for them to read unfamiliar words and build up to more and more challenging words. In particular, a specific approach referred to as “systematic phonics instruction” seems to be most effective. Systematic phonics instruction means teaching letter-sound connections in a specific order.

What Can I Do as a Parent?

Focus on phonics: Teach your child letter sounds and how to break words down into individual sounds and then blend those sounds together. Do not suggest that children “guess” the correct words based on the pictures or clues from the sentence. Research finds that this strategy is not as effective as phonics instruction in teaching children how to read.

Don’t worry as much about “sight words”: 96% of words in the English language are decodable in some way. What does that mean? MOST words in English can be sounded out. Learning words by their sounds rather than their shape is likely to be easier for children and support the development of reading fluently and reading comprehension. Check out “Heart word magic” for free videos one how to teach your child “tricky” words, such as “you” and “would.”

Use a phonics-based book: If you would like to teach your child to read yourself, research finds evidence that a phonics-based book called “Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons” can be an effective way to teach children how to read, even for children at risk for reading difficulties. Other examples of phonics-based books include “Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers” by Louisa Cook Moats Ed.D.and Dr. Susan Brady Ph.D., and “Know better, Do Better”. By David and Meridith Liben.

Praise your child’s hard work and effort: Learning to read is a very difficult task and research finds that children show more persistence in difficult tasks when you praise their hard work, effort, and strategy. Be careful not to praise their innate reading ability or label them as a “good reader” since this type of praise may make them more likely to give up when reading becomes difficult (since they assume they must not be a “good reader” after all). Instead, say something like “You have been practicing your reading every night and it really shows!” or “I could tell that you had to really think to sound out that word and you got it without any help… great work!”

Build your child’s spoken language skills: As your child is learning to read, continue to work on your child’s spoken language skills through conversation, play, audiobooks, and listening and telling stories. Research finds that spoken language is linked to improved reading skills. Research also suggests that when children already know a word’s meaning, they learn to read the word more quickly.

Practice “invented spelling: Allow your child to practice “invented spelling” (meaning that they guess how to spell words based on the sounds they hear rather than focusing on the correct spelling and that you do not correct their spelling). Research shows that “invented spelling” helps children learn how to read.

Practice, practice, practice: For your child to go from a novice reader to a fluent reader, they need as much exposure to letter sounds, reading, and print as possible. Practice could include: reading a book, playing a phonics game, rhyming and syllable games, and hands-on phonics activities. Although your child is hopefully practicing reading everyday at school, practicing reading out of school is essential as well.

Ask your child’s school what approach they use: Research finds that the systematic phonics approach has been found to be most effective for early readers. If your child’s school uses a different approach, present them with this research and advocate for a change.

What Can I Do With My Preschooler So They are Ready to Learn How to Read?

Read books that your child is interested in: Read with your child to expand their vocabulary and increase their love of reading. Research suggests that reading aloud to children during the preschool years is related to later reading skills. Create routines around reading. For example, read before bedtime or during quiet time. Make books readily available throughout your house, including places like the car or bathroom! However, remember that reading to your children and making books available will likely not teach them to read by itself.

Start pointing out letters and talking about letter sounds: Incorporate letters and letter sounds into your everyday life. Just try to keep it fun and low pressure. You don’t have to use worksheets or flashcards with your preschooler. Instead, focus on teaching the letter sounds rather than teaching letter names. For more information, see: “Phonemic awareness and letter knowledge in the child’s acquisition of the alphabetic principle” and “Acquiring the alphabetic principle: A case for teaching recognition of phoneme identity”.

Build your child’s vocabulary through conversation and play: Children with larger vocabularies have an easier time learning to read so make sure to introduce your child to new words everyday through conversation and play. Research finds that the more words your child knows, the easier it may be for them to learn how to read.

Have fun with sounds: Work on rhyming, counting the number of syllables in a word, singing songs with funny sounds, and recognizing when the “beginning sounds” of words are the same. For more information, see: “Letter names and phonological awareness help children to learn letter–sound relations.”

Important Notes

There is a fine line between not pushing our kids to read before they are developmentally ready and not providing them with early intervention if they are at risk for a reading disability. If you are concerned about your child’s reading or phonics ability or if they are 7 or older and still struggling, consult with their teacher and/or a reading specialist as soon as possible. It also certainly will not hurt your child to start introducing phonics concepts in a fun and engaging way at any age. Finally, the research described above applies mostly to learning to read in the English language.

Expert Reviewer

All Parenting Translator newsletters are reviewed by an expert in the field to make sure they are as accurate and as helpful for you as possible. Today’s newsletter was reviewed by reading specialist, Kaley Clarfield. Kaley Clarfield is a literacy specialist, kindergarten teacher, and mother to four children. She helps parents and teachers to improve their children’s learning through fun, hands-on activities. Check out her website, her Instagram, and her TikTok for additional learning resources and fun, engaging activities you can use to teach your child!

Wondering how you can support Parenting Translator’s mission and/or express your gratitude for this service? It’s easy! All you have to do is share my newsletter with your friends and/or on your social media!

Thanks for reading the Parenting Translator newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive future newsletters and support my work.

Also please let me know any feedback you have or ideas for future newsletters!

Welcome to the Parenting Translator newsletter! I am Dr. Cara Goodwin, a licensed psychologist with a PhD in child psychology and mother to three children (currently an almost-2-year-old, 4-year-old, and 6-year-old). I specialize in taking all of the research that is out there related to parenting and child development and turning it into information that is accurate, relevant, and useful for parents! I recently turned these efforts into a non-profit organization since I believe that all parents deserve access to unbiased and free information. This means that I am only here to help YOU as a parent so please send along any feedback, topic suggestions, or questions that you have! You can also find me on Instagram @parentingtranslator, on TikTok @parentingtranslator, and my website (www.parentingtranslator.com).

DISCLAIMER: The information and advice in this newsletter is for educational purposes only and is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical, mental health, legal, or other professions. Call your medical, mental health professional, or 911 for all emergencies. Dr. Cara Goodwin is not liable for any advice or information provided in this newsletter.