Is Disney "Bad" for our Kids?

The research behind Disney princesses (and princes), movies, and TV shows

It is hard not to love a Disney movie. It is entertaining for both kids and adults and often has a heartwarming message. Yet, it is also hard not to wonder if some of the messages and storylines in these movies have a negative impact on children. Many people argue that Disney promotes consumerism, negative female gender stereotypes, toxic masculinity, and unrealistic body standards. So does the research provide any insight into whether Disney movies, TV shows, and merchandise have a positive or negative impact on children?

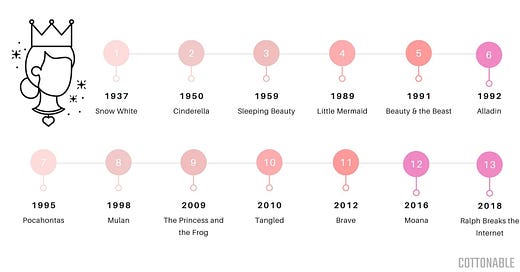

Disney Princess Timeline

Source: Cottonable

Concerns about Disney Princesses (and Princes)

Research finds that 50% of young girls engage with media related to Disney princesses at least once per month and 29% of young boys engage with this type of media once per month. It is so common that only 4% of girls and 13% of boys report never engaging with princess media.

One concern about Disney princesses is that they may have a negative impact on body image. Most Disney princesses have an unrealistic body that often includes a tiny waist-to-hip ratio (even tinier than Barbies). In addition, the waist-to-hip ratio for Disney princesses is less than that of Disney female villains, suggesting that these movies may promote the “skinny is good” stereotype. The Disney princess dolls also tend to be very thin with tight clothing and high-heeled shoes. This is concerning since research finds that exposure to unrealistically thin bodies in media may make some women more likely to report feeling bad about their own bodies.

A second common concern is that Disney princesses may promote negative gender stereotypes about women. Disney princesses have historically conformed to traditional gender roles (being portrayed as physically weak, attractive, nurturing, submissive, and fearful). Disney princesses have also been portrayed as being more valued for their physical appearance than other traits. Again, this pattern seems to be improving in recent years, with films placing more value on female characters’ skills and intellect (for example, Moana and Raya). Research finds that more recent Disney princesses have been more independent, less focused on romantic relationships, and just as likely to be a “hero” as the male characters. When research includes these more “modern” princesses, they find no difference between female and male characters in intelligence, ability, or story role (yet they still find differences in terms of occupations, leadership, and attractiveness). However, research suggests that these more “progressive” female characters may not change children’s perception of a “princess” and children may not even view characters such as Moana as “princesses.” In addition, even in more recent years, there are still more male characters than female characters in Disney movies and a linguistic analysis found that male characters tend to speak more than female characters in most Disney films (see graph below).

Source: Fought & Eisenhauer

In addition, many Disney movies do not pass the “Bechdel Test”. The Bechdel Test is a measure of gender stereotypes in a movie. The Bechdel test requires that, in a movie: 1) there are at least two female characters, 2) the two female characters have a conversation, and 3) the conversation is about something other than men. For example, Aladdin includes only one female character with a speaking role, and the Lion King includes several female characters yet they do not interact, so both would fail the Bechdel Test. Exceptions include Brave, Mulan, Frozen, and the Princess and the Frog.

Disney princess movies also tend to have “hyper masculine” princes or male characters. These characters tend to be aggressive, strong, brave, unemotional, and rejecting of anything feminine. This is concerning since men who adhere to hyper-masculine norms may have more negative attitudes towards women. However, like the female characters, the male Disney characters seem to be changing in recent years with characters such as Kristoff in Frozen, who show weakness and emotion.

The Impact of Disney Princesses (and Princes) on Child Development

So we have discussed the potential concerns about Disney media and why it might impact children, but does research actually find any links between engaging with Disney media and child development? A researcher named Dr. Sarah Coyne addressed this question through two longitudinal studies (translation: studies that follow children over time to study developmental trends). In her first study, the research team found that 4- and 5-year-old children who watched more TV shows and movies involving Disney princesses showed more stereotypically feminine behavior one year later, such as focusing on beauty/appearance, showing more kind and helpful behavior, and being more interested in female domains such as cooking and child care. Although there is nothing “wrong” with stereotypically feminine behavior, the researchers expressed concern that adhering to these stereotypical gender roles may make children feel limited in what they can do in the future.

However, a follow-up study when the children were 10 and 11 years old suggests a different result. Specifically, the researchers found that girls who were more interested in princesses at 4 to 5 years actually showed more egalitarian attitudes about women (seeing women and men as equal) at 10 to 11 years. The researchers also found that children from lower income families who engaged more with princess media showed more positive body image and less acceptance of hyper-masculinity.

Yet, one issue with these longitudinal studies is that children were not randomly assigned to engage with princesses. The children and families who choose this type of media are different from those who do not. One study randomly assigned children to watch a brief princess video with appearance-related content (like the scene in Beauty and the Beast where Gaston says that Belle is the most beautiful girl in the world) or another video without appearance-related content (like Dora the Explorer). They found that watching the Disney clip did not increase girls’ appearance-related concerns. Another study found no impact on toy preference, prosocial behavior, or perseverance when girls were randomly assigned to dress up in Disney princess costumes. However, these studies are limited since children were only briefly exposed to the video clip and the costumes in the laboratory rather than a childhood full of these influences.

TRANSLATION: Further research is needed on the topic, but there is currently no consistent research linking watching movies or TV shows with Disney princesses to negative gender attitudes or body image in young children.

The Messages of Disney Movies

Many parents are also concerned about the messages and themes of Disney movies. Although there is usually a “happy ending,” many Disney movies involve aggression, promotion of stereotypes, a focus on unrealistic romantic relationships, absent parents, and portraying some people as “villains.” It seems that we should take these criticisms seriously since Disney movies represent some of the first stories that our children hear. So are the messages from these movies positive or negative, and what impact might these messages have on our children?

Indeed, research finds that many Disney movies (particularly older movies) promote gender, racial/cultural, and socioeconomic class stereotypes. Most Disney movies also involve frequent negative references to mental illness (such as calling characters “crazy” or “nuts”). Disney movies also tend to demonize anyone who engages in “bad” behavior, with 74% of Disney movies referring to someone as “evil” with an average of 5.6 “evil” references per film. This is concerning because we would not want our children to label someone who makes a mistake as “evil” or “bad” (or perhaps even worse, to label themselves as “evil” or “bad”).

Research also finds that Disney movies on average involve 9 instances per hour of indirect aggression (gossiping, spreading rumors, excluding others). However, indirect aggression in Disney movies is typically shown in a bad light and most often used by villain-like characters, suggesting it may be less likely to be imitated by children.

On the other hand, research finds that most Disney movies (73%) include messages about loving yourself and others, and 27% include themes related to morality or values. Disney movies also have an average of one prosocial act per minute (translation: a prosocial act is anything that involves helping, cooperating, sharing, comforting or giving to others) . This is important since prosocial behavior in media is associated with more positive behavior and attitudes in children

One research study even found that when children were randomly assigned to watch a Disney movie clip showing one character helping another, they were more likely to help a friend.

Disney may even have a positive impact on adults. Research finds that when adult women were randomly assigned to watch Disney movies during chemotherapy, they were less tense and worried less. They also showed a higher quality of life during treatment and less fatigue.

TRANSLATION: Disney movies may promote stereotypes and include indirect aggression yet may also contain prosocial messages.

Overall Translation and Practical Tips

The research on Disney is both concerning and reassuring. As with all parenting decisions, the research is only there to help inform our decision, rather than make the decision for us. If Disney movies and TV shows make you uncomfortable and/or don’t align with your family values, it would be a reasonable decision to not allow this type of media. However, if you love Disney despite its potential limitations and want to share this love with your child, the following research-backed tips may help you to feel more comfortable about some of the concerns listed above:

Decide in advance which movies and TV shows you will allow your child to watch, given your own family values and your understanding of your child. You may only allow movies with main characters that defy gender stereotypes, or you may prefer movies that have a prosocial message (such as Moana). Either way, it is always easier to make these decisions in advance rather than debating with your child or parenting partner in the moment.

Watch Disney movies and TV shows with your child using a research-backed strategy called “active mediation.” Active mediation means discussing the characters’ choices or general themes with the goal of promoting critical thinking in children. Active mediation while watching TV shows and movies helps children to become “critical consumers” of media. Examples of active mediation can include asking about the consequences of the characters’ “bad” choices (“Will that choice actually make them happy? How will it affect others around them? What could they have done instead?”), challenging stereotypes (“Does it seem like that character is making an assumption based on looks?” Do you think that is true of all people who look like that character?”), and praising the characters’ positive behavior (“I love how they help the animals too” or “Wow, it’s amazing that they would help other characters even though they are scared”).

When watching Disney shows or movies (or any media that is overly focused on appearance), help your child to notice and focus more on personality qualities of the characters (such as being brave, strong, kind, or generous) rather than physical appearance. Point out when characters have bodies that are “unrealistic” and explain that appearance isn’t as important as some of these movies or shows may suggest.

Help children to distinguish between reality and fantasy in Disney movies. Some scenes in Disney movies may be scary or disturbing for young children. These scenes may cause nightmares or increase feelings of fear. Although it may seem obvious to you, make sure to explain to your children that scary scenes are “make-believe” and would not happen in real life. Research finds that young children get better at distinguishing fantasy vs. reality when you provide more information. For example, you could say “You see how the people are flying in this movie? That would never happen in real life, so you know this is just a pretend story” or “Have you ever seen a monster like that in real life? That’s how you know that this monster is just make-believe”.

If a theme or message in a movie or TV show does not align with your family values, explain that to your children and talk about it. For example, I will never forget my feminist mother explaining to my sister and me after watching Cinderella that marriage is not the solution to every one of life’s problems. Researchers have suggested that parents can use the themes and messages from Disney movies as a way to jumpstart important conversations with children (see here for a cheat sheet with all of the major themes/messages from Disney movies). You can use Disney movies to discuss both when the message is consistent with your family values/beliefs and when it is not. Research suggests that these types of conversations are most effective when parents support the child’s autonomy (when parents explain their reasoning and ask for their childrens’ feelings and perspectives).

Help your child to understand that people are not “good” vs. “bad” or “princesses/princes/heroes” vs. “villains.” Instead focus on their actions, choices, and thought patterns (“Was that a good choice?”, “That decision didn’t seem very thoughtful”, “Was he/she thinking about others when he/she did that?” or “It seems like that character made a mistake”).

Expert Reviewers

All Parenting Translator newsletters are reviewed by experts in the field to make sure they are as accurate and as helpful for you as possible. For this newsletter, we were fortunate enough to have two expert reviewers.

Dr. Jacqueline Nesi is a clinical psychologist and professor at Brown University, and the author of the popular weekly newsletter Techno Sapiens, about technology, psychology, and parenting. Her work focuses on the role of technology in kids’ relationships and mental health, and on how parents can help. She is also the co-founder of Tech Without Stress (@techwithoutstress), a company that provides online resources and courses to help parents feel more confident raising kids in the digital age.

Dr. Kristyn Sommer has a PhD in Developmental Psychology and her research focus on exploring how children engage in social learning from technology including screen time and social robots. Dr. Sommer is a postdoctoral research fellow in Psychology at Griffith University. Outside of the university, Dr. Sommer communicates science on social media on TikTok and Instagram.

Wondering how you can support Parenting Translator’s mission and/or express your gratitude for this service? It’s easy! All you have to do is share my newsletter with your friends and/or on your social media!

Thanks for reading the Parenting Translator newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive future newsletters and support my work.

Also please let me know any feedback you have or ideas for future newsletters!

Welcome to the Parenting Translator newsletter! I am Dr. Cara Goodwin, a licensed psychologist with a PhD in child psychology and mother to three children (currently an almost-2-year-old, 4-year-old, and 6-year-old). I specialize in taking all of the research that is out there related to parenting and child development and turning it into information that is accurate, relevant, and useful for parents! I recently turned these efforts into a non-profit organization since I believe that all parents deserve access to unbiased and free information. This means that I am only here to help YOU as a parent so please send along any feedback, topic suggestions, or questions that you have! You can also find me on Instagram @parentingtranslator, on TikTok @parentingtranslator, and my website (www.parentingtranslator.com).

DISCLAIMER: The information and advice in this newsletter is for educational purposes only and is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical, mental health, legal, or other professions. Call your medical, mental health professional, or 911 for all emergencies. Dr. Cara Goodwin is not liable for any advice or information provided in this newsletter.