Are the Pandemic Babies and Kids Okay?

The research behind how the pandemic impacted child development and what you can do about it as a parent

Source: Pexels/Tatiana Syrikova

The COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread disruptions across the world that led to financial strain, social isolation, and decreased support for families. These disruptions in turn led to increased stress in parents and caregivers and a mental health crisis among both adults and children.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, many parents and experts have raised concerns that the pandemic (and all of its terrible side effects) would also impact the development of children. Slowly, a body of research is coming out that can address these concerns. So what is the research telling us? Did the pandemic cause subtle changes in development that children will eventually compensate for OR did it cause serious developmental delays that may ultimately result in more children meeting criteria for developmental disabilities (translation: conditions that emerge in childhood but may result in lifelong impairment in functioning)? Today’s newsletter will discuss:

The research thus far on the impact of the pandemic on child development

How to know if your child has a developmental delay or disability (and what to do about it)

How parents and caregivers can help to enhance their children’s development after the pandemic

You can read the newsletter below or listen to the newsletter by clicking the button below:

Research on the Impact of the Pandemic on Child Development

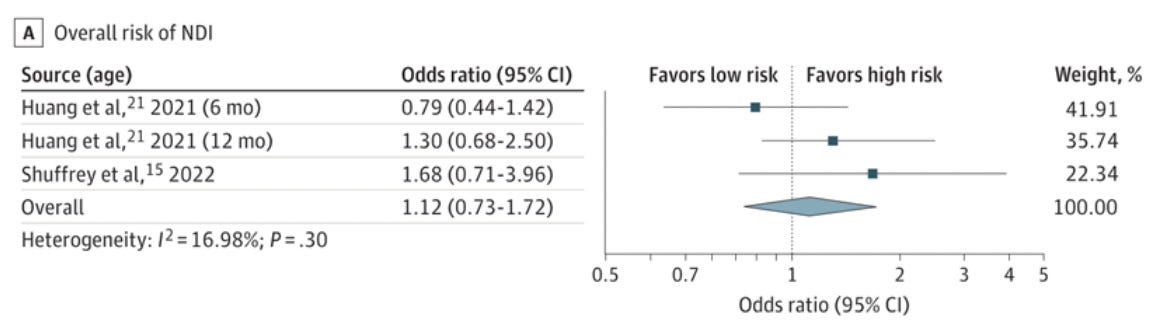

First, let’s examine the research on the infants born during the pandemic. The largest study that we have on the impact of the pandemic on child development is a meta-analysis (translation: a study that combines data from all previous relevant studies) that included 11,438 infants born during the pandemic and 9,981 infants born before the pandemic. When the data was combined across studies, there were no overall differences in development in the first year of life, meaning there was no increased risk for a developmental disability in the children that lived through the pandemic (see graph below). However, the infants born during the pandemic did show an increased risk for delayed communication skills. Yet, no differences were found between babies born before versus during the pandemic in terms of motor development, social-emotional development, and problem-solving. When you look at the graph below though, it is clear that there is a great deal of variation in the outcomes of children born during the pandemic (meaning some children thrived during the pandemic and some were severely impacted).

Source: Hessami K, Norooznezhad AH, Monteiro S, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and Infant Neurodevelopmental Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2022

This meta-analysis also found that infants who were potentially exposed to COVID-19 in the womb (meaning their mother contracted COVID-19 during pregnancy) showed no overall differences in development and no increased risk for developmental disability. Yet, they did show increased risk for an impairment in fine motor skills. However, since the placenta seems to protect most babies from COVID-19, it is possible that this finding reflects other differences between mothers who were and were not infected by COVID-19 such as being an essential worker during the pandemic.

Research has also examined specific developmental milestones in social communication and found that infants born during the pandemic showed impaired social communication skills at 12 months. Specifically, when compared to 12-month-olds born before the pandemic, fewer 12-month-olds born during the pandemic had spoken their first word (76.6% vs 89.3%), pointed (83.8% vs 92.8%) or waved goodbye (87.7% vs 94.4%). However, babies born during the pandemic showed some signs of advanced gross motor development with more babies born during the pandemic crawling at 12 months (97.4% versus 91%). No differences were found for other developmental milestones including standing alone, stacking blocks, feeding themselves, responding to their name, and using a pincer grasp (translation: picking up small objects between the thumb and pointer finger).

Another study looked at the duration of the infant’s first year lived during the pandemic and found no relationship between how long they experienced the pandemic and child development (including language and social-emotional development) or maternal mental health or stress at 12 or 24 months. They even found no relationship between disruptive life events related to the pandemic and child development (translation: children who experienced more negative events as a result of the pandemic did not show more developmental problems). However, more disruptive life events during the pandemic was associated with more anxiety and depression in mothers.

This newsletter is primarily focused on infants and toddlers but it is important to mention that school-age children were also impacted by the pandemic. A meta-analysis (combining the results of many different studies across different countries) found that school-age children across the world lost about 1/3 of a school year’s learning during the pandemic on average and they have not seemed to recover from these losses even two years later (see results in the graph below). These learning deficits are particularly significant for children from lower income families. Research also finds that the learning losses seem to be greater in math than reading.

Source: Betthäuser, B.A., Bach-Mortensen, A.M. & Engzell, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav (2023).

Research finds that even adolescents’ development was impacted by the pandemic. Adolescents who lived through the pandemic showed not only increased depression and anxiety but also “advanced brain age” (translation: the brain maturing faster than would be expected). Although at first this may seem positive, “advanced brain age” is common in children who have experienced violence, neglect, or other traumatic experiences. In other words, the stress of the pandemic may have unnaturally sped up their brain development

Research also found a pattern of worsening mental health and increased behavioral problems during the pandemic across all children 18 years and younger. This was particularly true for families that experienced more hardships during the pandemic.

TRANSLATION: Overall, babies and toddlers did not show significant global developmental delays during the pandemic, yet there is some evidence for delayed social and communication development. The data on babies and toddlers indicates a wide range of variation in outcomes– some children seemed unaffected by the pandemic and some children seemed severely impacted. Older children also showed evidence for learning loss and differences in brain development as a result of the pandemic. Children of all ages showed , increased mental health and behavioral problems,

Why Did This Happen?

There are many possible reasons the COVID-19 pandemic could have negatively impacted children. Some of the most likely explanations include:

Parent mental health: The COVID-19 pandemic caused financial strain, social isolation, and decreased family support, which in turn increased parental mental health problems. Specifically, research found that anxiety and depression in new mothers was dramatically higher during the pandemic with 61% of new mothers experiencing anxiety and 43% of new mothers experiencing depression (compared to 14% and 16% of mothers pre-pandemic) (Fallon et al., 2021). Not surprisingly, mothers who experienced more negative events related to the pandemic (such as losing a job or child care) were more likely to experience mental health issues. Mental health issues in parents can contribute to less sensitive and responsive parenting which then negatively impacts child development.

Lack of access to health care, child care, and school: The pandemic closed many child care centers and schools, which undoubtedly reduced learning opportunities for children. The pandemic also made it more difficult for parents to access necessary health care and other services such as speech-language therapy, physical therapy, and parent education groups. The loss of any external support for parents may have also negatively impacted child development.

Job and Income Loss: Job loss and income loss during the pandemic were associated with less positive interactions between parents and children. Women from lower income families also experienced more symptoms of anxiety and depression during the pandemic and they were more likely to lose a job or income during the pandemic. Severe COVID-19 infections and deaths were also more common in lower income and ethnic minority families.

Lack of routine and structure and quality parent-child time: Children thrive on routine and structure and the pandemic disrupted a lot of family routines for children. Research found that practicing family routines during the pandemic predicted better mental health, even when controlling for income and mother’s depression and anxiety. This disruption of routine often resulted in parents replacing quality parent-child interactions (such as reading) with less quality interactions (such as screen time). Research found that parents who read less to their children and had more passive screen time during lockdown had children who showed impaired language development during this time.

Limitations of this Research

It is very important to note that the research from the pandemic may be limited for several reasons. First, most of the data on children’s development during the pandemic is based on parent report. Parents’ reporting of their children may be more negative because they may have a belief that something as extreme as a pandemic would have to be negative for children. It could also be that parents were spending more time with their children during the pandemic which allowed them to notice more developmental problems or be more concerned about their child’s development more generally.

Second, even studies that did not involve parent report may be biased. In these studies, they were comparing children assessed in normal conditions before the pandemic to children assessed during the pandemic with researchers wearing masks, staying behind plexiglass windows, and/or taking other precautionary measures that may have confused or distracted the children enough to result in lower scores during the pandemic. In addition, the people who were willing to come in during a pandemic may be more worried about their children’s development.

Third, the data clearly reveals that there was a great deal of variation in the outcomes for children. Some children flourished during the pandemic and some children experienced delays. We cannot assume that the entire generation of children is delayed.

Finally, the differences found during the pandemic could be a temporary decline and, in a few years, we could see no differences between the two groups. However, as I will explain later in this newsletter, it is important that we take action now to correct the developmental course of these children, rather than just assuming children are resilient.

How to Identify Developmental Delays & Developmental Disabilities

Before the pandemic, about 1 in 6 children were identified as having a developmental delay or developmental disability. And, even before the pandemic, the rates of developmental disabilities were increasing, with 16.2% of children having a developmental delay or disability in 2009 to 2011 and 17.98% in 2015 to 2017.

What is a developmental disability? How is it different from a developmental delay?

A developmental delay is when a child is consistently behind in acquiring skills in at least one of these areas: cognitive (IQ/problem-solving), social/emotional, speech/language, fine/gross motor, and activities of daily living. A global developmental delay means your child is experiencing delays in more than one domain. A developmental delay can mean your child is slightly delayed in developing certain skills and will catch up, or could be a sign that your child will meet criteria for a developmental disability.

A developmental disability is a specific lifelong condition characterized by impaired development in terms of physical development, learning, language, or behavior. The most common developmental disabilities are attention deficit disorder (9.5% of children), learning disability (7.9%), autism spectrum disorder (2.5%), stuttering (1.9%), and intellectual disability (1.2%). Developmental disabilities can also include cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and seizures. Developmental disabilities may be very mild or very severe.

So how do you know if your child has a developmental delay or developmental disability?

Parents should be concerned about the possibility of a developmental delay or disability when their child is not meeting milestones at the same time as other children their age. However, because this can be difficult for parents to judge, there are standardized lists of developmental milestones that parents can refer to. A great resource for developmental milestones is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. The CDC has milestones for each age on their website from 2 months to 5 years and an app called Milestone Tracker.

They even have a PDF you can print with a checklist for each age. Their milestone checklists are available in Spanish, Arabic, Brazilian Portuguese, Farsi, Haitian Creole, Hindi, Korean, Chinese, Somali, and Vietnamese.

Parents can also complete the Ages and Stages Questionnaire for free. It only takes 10 to 15 minutes and helps to highlight potential areas of developmental delays but also developmental strengths in the domains of communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving, and personal-social. The Ages and Stages Questionnaire is available in English, Spanish, French, Chinese, and Vietnamese.

What exactly are developmental milestones? Developmental milestones simply mean skills or tasks that most children can consistently do at a particular age (examples include smiling, rolling over, babbling, pretend play, or counting to 10). The CDC developmental milestones reflect what 75% of children can do at a particular age (in other words, 3 out of 4 children at that age meet that milestone). This means that many typically developing children will miss a milestone here or there, and that is usually not a cause for concern. However, a pattern of several missing milestones may be a cause for concern. When in doubt, parents should always reach out to their pediatrician or seek an evaluation.

One important note about the CDC developmental milestones. Many speech language pathologists think that the new language milestones are too lenient. For example, at 18 months children are now only expected to say 3 or more words (in addition to mama and dada) while research indicates that 75% of children say 37 words or more at 18 months. At 30 months, children are only expected to say 50 words, when 75% of children say 412 words or more at 30 months. Therefore, it may be more helpful to follow these research-backed guidelines.

When children are young, it can be difficult to determine whether it is a developmental delay or developmental disability but early intervention is necessary in both cases. Some children with developmental delays or disabilities may “catch up” to their peers with early intervention so it is critically important that developmental disabilities and delays be identified and treated through early intervention.

What To Do If You Are Concerned About Your Child

Many children were likely missed by early intervention services during the pandemic. Children were less likely to see their primary care physician during the pandemic, which likely resulted in fewer referrals to early intervention. It is very important that the children who were “missed” during the pandemic are now identified and referred to early intervention. It is never “too late” to start intervention and we shouldn’t just assume that getting “back to normal” will be enough to change the developmental path of any children who experienced developmental delays during the pandemic. It is very important that we not simply dismiss delays as being a side effect of the pandemic (aka “he’s just a pandemic baby… aren't they all slow to talk?!”) or assume that these children will be resilient. Even though developmental delays may be more common after the pandemic, children still need to be identified and referred to early intervention. In order to reverse the impact of the pandemic, we likely need to go above and beyond to help these children and actively work to make up for lost time.

The evaluation process for developmental delays is different in every country. In the United States, early intervention services provide free evaluations for children 0 to 36 months and, if your child meets criteria for a developmental delay or disability, they will provide free services (usually in your home). In the United States, if your child is over 3 years old, you can request a free evaluation from the public school system. Call any public elementary school and say “I am concerned about my child’s development and I would like to have my child evaluated through the school system”. If eligible, you will receive free services through the public school system. You do not need a referral from your pediatrician but can seek out these services on your own.

It can be scary to seek out an evaluation but it is important to remember that, at best, an evaluation will put your mind at rest and, at worst, it will get their child the services that will help them. You do not have to tell anyone the results of the evaluation unless you want to. Finally, it is important to remember that developmental delays or disabilities are NOT caused by parents and do not reflect anything you did “right” or “wrong” as a parent.

Three Ways Parents Can Advance Development

If you are concerned about your child’s development, you should always seek help from professionals. However, if your child does not meet criteria for services or if you have to wait for an evaluation or services (unfortunately waiting lists for early intervention are all too common), here are three ways you can help to advance your child’s development:

Increase the language: Research consistently finds that the more you talk to your child, the more advanced language skills they will develop. In particular, research suggests that you should focus on back-and-forth conversations with your child (even if their response is only a babble or some type of movement). You don’t have to practice language in formal lessons or using flashcards– just work more language into your everyday routines.

Read to your child: Research suggests that reading to your child is associated with improved language and academic skills. Create a routine in which you read to your child at least once per day. Make sure you are not just reading the words but talking to your child about the book and allowing them to make comments or ask questions.

Play, play, play: Get on the floor and play with your child whenever you have a chance. Follow their lead in play and allow them to choose the activity and how the play goes. Research finds that this type of child-directed play helps to advance cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development.

Expert Review

All Parenting Translator are reviewed by experts in the topic to make sure that they are as helpful and as accurate for parents as possible. Today’s newsletter was reviewed by Rebecca Berlin, PhD. Dr. Berlin received her PhD from the University of Virginia School of Education and has served as a special education teacher, home visitor, child assessor, autism specialist and school administrator. She has conducted research on the teacher-child interactions, as well as play and story based interventions for improving social skills and classroom quality. She currently serves as the Executive Director for the Parenting Translator Foundation.

Wondering how you can support Parenting Translator’s mission and/or express your gratitude for this service? It’s easy! All you have to do is share my newsletter with your friends and/or on your social media!

Thanks for reading the Parenting Translator newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive future newsletters and support my work.

Also please let me know any feedback you have or ideas for future newsletters!

Welcome to the Parenting Translator newsletter! I am Dr. Cara Goodwin, a licensed psychologist with a PhD in child psychology and mother to three children (currently an almost-2-year-old, 4-year-old, and 6-year-old). I specialize in taking all of the research that is out there related to parenting and child development and turning it into information that is accurate, relevant, and useful for parents! I recently turned these efforts into a non-profit organization since I believe that all parents deserve access to unbiased and free information. This means that I am only here to help YOU as a parent so please send along any feedback, topic suggestions, or questions that you have! You can also find me on Instagram @parentingtranslator, on TikTok @parentingtranslator, and my website (www.parentingtranslator.com).

DISCLAIMER: The information and advice in this newsletter is for educational purposes only and is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical, mental health, legal, or other professions. Call your medical, mental health professional, or 911 for all emergencies. Dr. Cara Goodwin is not liable for any advice or information provided in this newsletter.

Thank you for sharing this important research on the the impact of the pandemic on child development. I fear that this is an impact that we will be facing for the next 18 years as this generation moves through the early childhood and K-12 education system. The other aspect of this is the large number of children who were already identified with the delays and disabilities who did not receive the level of services they needed, as well as those children who were awaiting evaluations that were postponed, delayed, and missed.

Great question! I don’t know of any research comparing the two screening tools. The CDC is more of a checklist while the ASQ-3 will give you a score that gives you a quantitative measure of your child’s risk for developmental delay.