Do Kids Really Get a “Sugar High?”

The research behind whether sugar really impacts children’s behavior

This week’s newsletter is a recycled past newsletter in honor of Halloween week and because this is still one of the most common questions that I get on my Parenting Translator platform!

Nearly every parent has had an experience in which their child eats more sugar than usual and seems to be bouncing off the walls or has an uncharacteristic tantrum or meltdown. We might laugh it off as a “sugar high” or even swear that they will never be allowed to eat that particular sugary food or that particular quantity of sugary food again. This experience commonly happens at holidays, such as Halloween and Easter, when candy and sugary treats may be provided without restriction.

So does research back up this incredibly common experience? Does sugar really negatively impact children’s behavior?

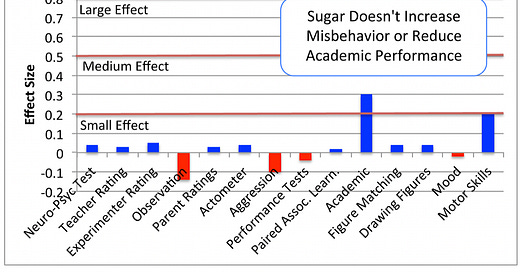

Source: The Wing Institute, based on the results of Wolraich, M. L., Wilson, D. B., & White, J. W. (1995). The effect of sugar on behavior or cognition in children. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274(20), 1617-1621

Surprisingly, research consistently finds that eating sugar does not impact the behavior of children. A meta-analysis (a study that combines data across multiple studies) found that sugar did not seem to significantly impact the behavior, cognitive functioning, or academic performance of children. See graph above which only shows a small positive impact on academic skills (yet there was only one study showing a significant positive impact so it is important not to read too much into these results). This meta-analysis included 23 studies involving over 500 children. Some of these studies were conducted in a laboratory and some in the child’s school. All studies included in this meta-analysis were experiments that compared children’s behavior, cognitive, and academic performance after eating sugar versus a placebo (usually aspartame or saccharin).

So this meta-analysis suggests that sugar does not seem to impact children on average but are there some children who are more sensitive to sugar and thus react negatively to it?

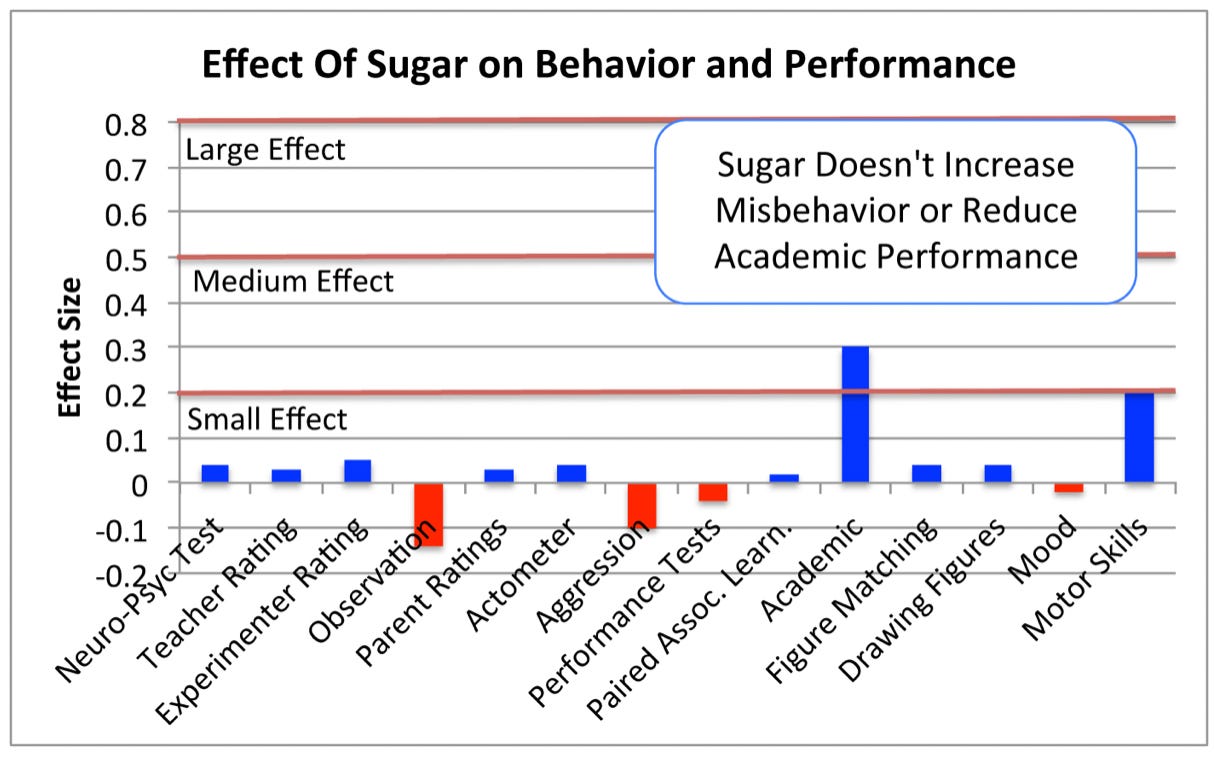

To address this question, one study compared school-age children who were reportedly more sensitive to sugar versus preschool children who were not reported to be sensitive to sugar. The researchers then asked families to implement the following diets for three weeks each (see graph below):

A diet high in sugar with no artificial sweeteners

A diet low in sugar but high in aspartame (an artificial sweetener which has also been suggested as a cause of hyperactivity in children)

A diet low in sugar but high in saccharin (another artificial sweetener which has not been linked to hyperactivity)

Source: Wolraich, M. L., Lindgren, S. D., Stumbo, P. J., Stegink, L. D., Appelbaum, M. I., & Kiritsy, M. C. (1994). Effects of diets high in sucrose or aspartame on the behavior and cognitive performance of children. New England Journal of Medicine, 330(5), 301-307.

Parents were told to avoid any artificial coloring, additives, and preservatives on all diets. The researchers found no differences in behavior, attention, hyperactivity, mood, executive functioning or academic performance in either typical preschool children OR for the sugar-sensitive children on any of the three diets. In fact, the researchers tested 39 different variables and found no difference among the diets on any of these variables.

Some studies even find behavioral and academic benefits immediately after eating sugar. One study found that children who drank a high-sugar beverage showed improved memory and classroom performance when compared to children who drank a sugar-free drink. Another study examined the impacts of sugar on the behavior of juvenile delinquents. The researchers found that adolescents who ate a high-sugar breakfast, particularly those with teacher-reported hyperactivity, showed improved behavior on some measures when compared to children who ate a sugar-free breakfast. Finally, research also found that children who ate a high-sugar snack showed improved memory compared to children who ate an artificially sweetened placebo. Researchers speculate that the brains of children may require more glucose to operate efficiently (translation: glucose is what your body breaks down all sugary foods into and glucose is the primary source of energy for the brain), thus explaining why behavior and academic performance may be improved after consuming sugar.

However, critics of the studies described above may argue that these experiments do not represent how sugar is consumed in “real life” and that even following children for three weeks is too short of a time period to see significant results. Another limitation of these experiments is that they compare the impact of sugar to a placebo which is most often an artificial sweetener such as aspartame or saccharin. They use artificial sweeteners because it is essential that the placebo taste sweet so that the research participants’ own expectations don’t impact the results. It remains unclear the impact that these artificial sweeteners may have on behavior.

Addressing some of these concerns, another study examined links between sugar consumption in children age 8 to 12 years as reported by children from their daily lives and behavior and sleep. The researchers found that 81% of the children in this study exceeded the recommended sugar intake (with the average child consuming the amount of sugar in 22 Oreo cookies per day!). Yet, sugar consumption was not correlated with any behavioral or sleep measures. It is important to note that this study is correlational, meaning that this cannot be interpreted as evidence that sugar does not cause behavioral and sleep problems.

How Can This Be True?

The research on sugar and behavior is limited but consistently shows that sugar is not linked to behavior in children. You may be thinking of a specific instance of a “sugar high” that undoubtedly caused hyperactivity and challenging behavior and wondering how nearly every parent has experienced this phenomenon if sugar really has no impact on behavior.

One reason could be parental expectation. Research finds that, when children are given a placebo and their parents are told it is a high dose of sugar, parents report their children to be significantly more hyperactive. Social reinforcement may encourage these expectations. For example, when a parent says, “It seems like he is on a sugar high,” other adults around them are likely to back up this observation (“Of course —that happens to every child on Halloween”).

In addition, as parents we are often looking for an explanation for our children’s behavior. Rather than just accepting that children’s behavior is unpredictable, we look for a reason so that we can understand it and make sure it doesn’t happen again. This tendency (which all humans have) is called “intolerance of uncertainty.” We look for explanations because we can’t handle the uncertainty that it could happen at any time. Supporting this idea, research finds that mothers with more cognitive rigidity (that is, those who might be more intolerant of uncertainty) are more likely to expect behavior changes with sugar consumption.

This experience may also be explained by the tendency of have a “confirmation bias”. A confirmation bias means that we tend remember experiences that match our expectations and do not pay attention to or forget experiences that don’t. So this means that you remember all of the times that your child lost their mind after eating sugar but not all of the times that they stayed calm.

Finally, the situations in which children typically consume a lot of sugar (such as holidays and birthday parties) may make a child seem more hyperactive due to excitement or sensory over-stimulation. In other words, it may be the situation and not the sugar itself that causes the behavior.

The Health Impacts of Sugar

It is very important to mention that a diet high in sugar is known to have a negative impact on children’s health. Research finds that a diet high in sugar is associated with an increased risk for obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and dental cavities.

The World Health Organization recommends that added sugar make up less than 10% of an individual’s total calories and that less than 5% would further reduce risk of dental cavities.

So How Do I Handle Sugar with my Kids?

Sugar is complicated topic and you have to make the best decision for your child and your family. Your child may have health issues that make it particularly important to avoid sugar or you may believe that the health risks are so serious that it makes sense to avoid sugar entirely. You may also strongly believe that your child responds negatively to sugar and the research described above doesn’t necessarily prove you wrong (research typically only shows what is true for most children and not allchildren). However, if you want to provide sugar for your child in moderation, then the following tips may be helpful to you:

Use “covert control” of sugar rather than restriction to help your child learn to eat sugar in moderation. Research suggests that parents should avoid restricting all sugary foods from a child’s diet. Research finds that, when parents restrict sugary foods, their children might eat less in the short-term but become more preoccupied with the food over time. Another study found that when parents restricted food, children show excessive eating of these restricted foods when they were given access to them.

So how do we avoid restricting intake of sugar without our child eating a whole package of Oreos at every meal? Instead of restriction, researchers recommend that parents use “covert control” to manage their child’s sweet intake. “Covert control” can include not buying a lot of sweets to have around the house, avoiding eating sweets yourself in front of your children, or avoiding places that sell sweets such as candy shops. Research shows that these more subtle approaches are effective at increasing healthy eating patterns.

Consider offering high-sugar foods with meals rather than as special “treats” to minimize their novelty and allure. By making foods like candy, desserts, and other treats more available as part of a meal, your child learns that they can be included in a healthy diet and should not be on a pedestal. Research finds that children actually eat less dessert when it is served with a meal than when it is served after a meal. To read more about the research on serving dessert with dinner and how to do so in practice, see How to Offer Dessert with Dinner to Toddlers.

Change your own perspective. Your own expectations may have an impact on your child. Be careful about your own reaction to your child eating sugar and your own expectations. Rather than seeing all sugar as “evil,” view it as an important energy source that is essential for your child in moderation.

Research finds that when mothers who believe their children are “sugar sensitive” are told their child was given sugar (yet they were actually given a placebo), the mothers showed more controlling behavior and criticism. Because controlling behavior and criticism are associated with more challenging behavior in children, it is possible that the parents’ own expectations cause the behavior rather than the sugar itself.

Try to find the cause of your child’s challenging behavior. Rather than simply blaming your child’s challenging behavior on sugar, it may be more helpful to try to find the cause of the behavior (common causes of challenging behavior include attention-seeking, sensory over-stimulation, trying to escape demands, or a lack of skills such as not knowing how to ask for help).

Parents should also examine how their own responses may impact their behavior. Are you providing too much attention to negative behavior rather than focusing on noticing the positive behavior? Are you being too controlling of your child’s behavior? If you continue to struggle with your child’s behavior, consult with a behavioral specialist or mental health professional, who may help you develop effective strategies to prevent and manage behavioral challenges.

Overall Translation

Although diets high in sugar are linked to many health complications in children, there is currently no consistent evidence that diets high in sugar are linked to behavioral or academic problems. Instead of completely restricting sugar, parents may want to try using “covert control,” offering high-sugar foods with meals, changing their own expectations and responses to their child’s behavior, and working to find the real cause of the child’s challenging behavior.

I first encountered these studies in Virginia Sole-Smith’s Fat Talk (a great book!). Thanks for this reminder!

This is a great article and a lot of useful information thank you for sharing it!!